In a week or so, I will begin work on a show in New York produced under the Equity Showcase Code, more on that in a later post. But the prospect of showcasing my work under this code reminds me a lot of what used to be called "Waiver Theater" in Los Angeles.

Both codes were invented by the stage actors' union at the request of its members, who wanted a way to show off their stage talents without being cast in a show which had, you know, a real paying contract. I worked more than once under the Waiver code in LA, back when there were tiny theaters all over the place using it. Equity has since changed the name of that code, and has clarified its rules, as the thing was egregiously abused for years. Back in the day, a Waiver show might run for months and months, with the producers raking in the dough from the box office, while the actors worked for free.

|

| The Odyssey Theatre Ensemble ran a production of Steven Berkoff's Kvetch for 8 years without paying an actor. |

I think the code is now called the "99-Seat contract" , as it can only be used in a theater seating 99 people or less, and the union finally realized that "waiver theater" left the impression that Equity was waiving all its rules and regulations, which it was not.

|

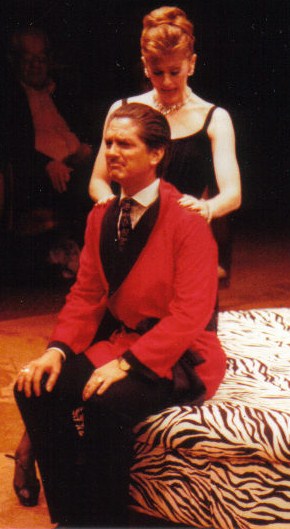

The only performing gig from which I have ever been fired was here, at the Ebony Showcase Theatre.

They ran a production of Norman, Is That You?, off and on, for years under the Waiver Code.

No actor was ever paid. |

I did six shows in waiver houses when I was living in LA, and those memories are coming back to me, as I prepare to spend the summer working under New York's version of that old Work-For-Free code.

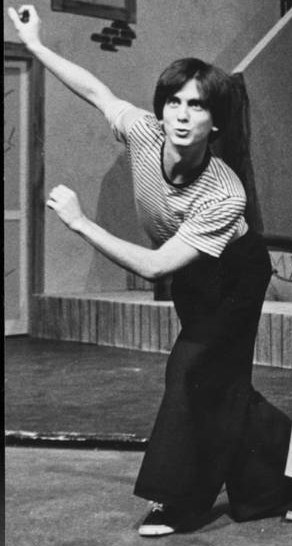

My first experience with the species was when I was only 18 or so. During my first year of college at California State University, Northridge, I began auditioning for on campus shows. I had some luck with student productions, landing in an original one-act right away.

My first experience with the species was when I was only 18 or so. During my first year of college at California State University, Northridge, I began auditioning for on campus shows. I had some luck with student productions, landing in an original one-act right away.

|

Charlie Martin-Smith played Toad in American

Graffiti. He cast me in my first show in college. |

The show was being directed by one of CSUN's celebrity students, Charlie Martin-Smith (you'd remember him from American Graffiti). I was going to spend most of my college years appearing in student-driven productions, as the faculty directors were never sure what to do with me.

At any rate, after finishing my CSUN debut performance in Have You Ever Seen A Panda? (yep, that was the name of the thing), I heard about an audition for a Waiver theatre in Chatsworth, CA, one of the burghs close to Northridge in the San Fernando Valley section of L.A. The group was called the Valley Theatre of the Performing Arts, a high-falutin' name for a company which operated out of a building which looked like it had been converted from a two-car garage.

|

| Somebody else's Interview. |

The only reason this group caught my eye was the fact that they were casting a show I was very interested in, a one-act called Interview, by French absurdist Jean-Claude Van Itallie. My California high school, Kennedy High in Granada Hills, had done a version of the show the year before I arrived there; I had seen pictures of that production and was intrigued. With nothing else on my plate on campus, I auditioned and was accepted into the production. The show actually included two one-acts by Van Itallie, the aforementioned Interview, and a companion piece called TV. In the first play, eight actors played either job interviewers or interviewees, and the point was to illustrate the facelessness of corporate America, and the futility of trying to maintain humanity in the workplace. In TV, three of us (including me) played employees of a television network whose sole job was to watch TV. The other cast members enacted the shows we were watching; ultimately, the audience was to be confused about which was which. Both these pieces, as I said, were part of the absurdist theatrical movement, so they were not written in a realistic, linear fashion (but both their themes are even more relevant today, I think).

The cast performed in both one-acts, under the umbrella title America, Hurrah! The show was an off-night production, which meant we were to perform only on Tuesdays. Still, as a Waiver production, this was considered to be professional, and I was quite full of myself for having landed the gig.

The cast performed in both one-acts, under the umbrella title America, Hurrah! The show was an off-night production, which meant we were to perform only on Tuesdays. Still, as a Waiver production, this was considered to be professional, and I was quite full of myself for having landed the gig.

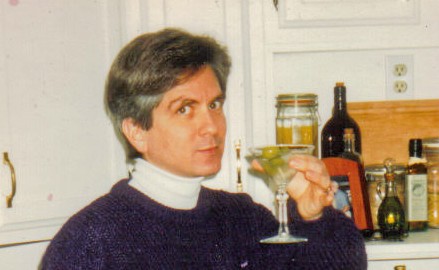

Very soon after we started rehearsal, my acting class at CSUN received a one-day audition workshop run by Bruce Halverson, who was the newest faculty member and a real go-getter in the department.

|

Bruce Halverson now heads the South Carolina

Governor's School of the Arts. |

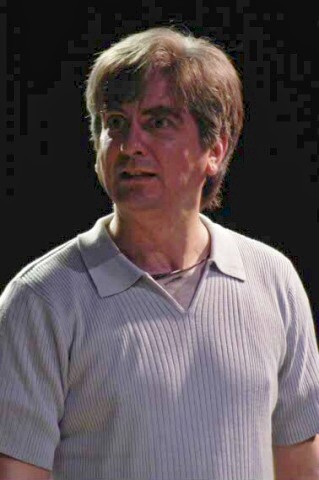

I had a great time during his workshop, and after class, he approached me. He was in the midst of auditions for the main stage production he was directing, the Feydeau farce A Flea In Her Ear. He wanted to make sure I was planning to audition. The show conflicted with my measly little one-night-a-week Waiver production, so I had to rather sheepishly decline. Bruce was a little startled that I would choose to do a couple of unknown one-acts out in Chatsworth, rather than appear on CSUN's main stage, but he certainly was not going to insist that I dump the off-campus gig.

|

Bruce had me in mind for the snotty butler in Flea In Her Ear.

My buddy Brad played it instead. |

I've made some lousy choices in my theatrical career, and that was one of them. I didn't have any guarantee that I would have been cast in Bruce's A Flea In Her Ear, but in retrospect, I think he was very interested in using me.

|

I eventually worked with Bruce on his

own show, Great American Travelin'

and Medicine Show. |

Bruce turned out to be one of the very few CSUN faculty members who had any value, and I was lucky enough to work with him a couple of years later in another play, but still, when I saw his hilarious show, I regretted not trying to be a part of it. That's not the only reason I regretted my decision.

A few weeks after my workshop with Bruce, we opened America, Hurrah!, to an almost empty house.

|

| The playwright's name was misspelled in the program. "Van Itallie" became "Van Itallic." A Freudian slip, or just lousy producing? |

We rarely had more than a dozen people attend any of our shows (why anyone thought people would go to the theatre on a Tuesday night in Chatsworth, of all places, to see a couple of avant garde plays, is anybody's guess). Our show was scheduled to run several months, ending in the summer. But one Tuesday, only about 4 weeks into the run (which meant, after only four performances, I'll remind you), we arrived at the theatre to be told that tonight would be our last night. The producers were shutting down the off-night show, and didn't care to give the actors any advance notice.

This illustrates one of the major flaws in what was known as the Waiver Theater Code: the producers could do such things without regard to the actors. They were not getting paid, so giving the cast a week's closing notice was unnecessary.

America, Hurrah! closed while A Flea In Her Ear was still in rehearsal, so I spent some time kicking myself for making the wrong choice, especially after the latter show opened on campus and was a substantial success.

In the four years I attended Cal State, Northridge, I was to perform in two more off-campus productions following America, Hurrah!, though neither of those productions was produced under the Waiver Code. But only a few months after graduating, I was invited to join another Waiver Theatre production, one which remains one of my fondest memories. Stay tuned for Part II of my Waiver Games.

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)