|

| This poster for the 1970 film was banned by many newspapers across the country. A more subtle poster replaced it (it's below) |

|

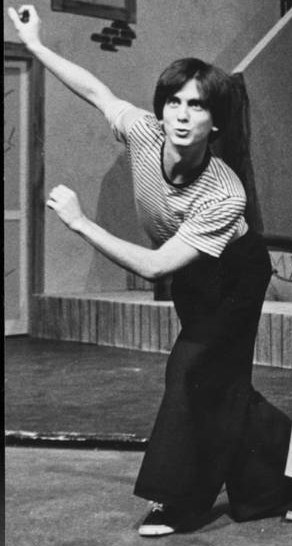

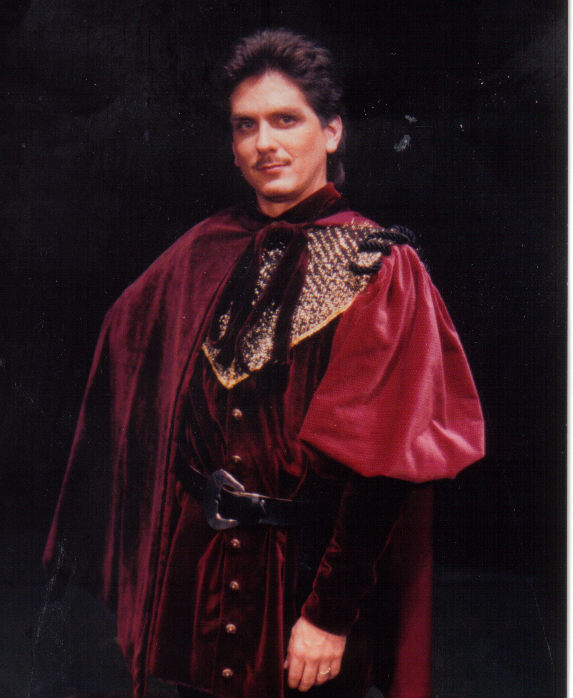

| Michael hosts a party for Harold. These two thoroughly nasty queens create the dramatic stimuli of the play. |

Gay activists such as the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights groups, disowned the bitchy, sad, and fairly unpleasant characters portrayed in The Boys in the Band. So our Boys became controversial not only in the mainstream, but also among the gay community; this controversy continues today.

I didn't know anything about this controversy when I first became aware of The Boys in the Band, when, at age 13, I opened the Sunday edition of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and saw this movie ad:

The first thing I can report about the Broadway production of Boys in the Band is this: it's friggin' hilarious. Somehow, the same text which comes off as vicious on film becomes enjoyably flippant onstage, at least initially.

Congratulations in no small part must go to director Joe Mantello, who has guided his cast to mine the laughs, and they have struck gold. The first half of the show (in what used to be its first act; playwright Mart Crowley has wisely trimmed the play a bit and removed the intermission) feels like Terrence McNally wrote it. Jim Parsons as Michael, the leading character, knows his way around comedy, and his first scene, opposite Matt Bomer, is full of laughs.

Except it can't. Many gay men of the generation depicted in this play have accused the playwright of displaying some very nasty stereotypes, as if all gay men of the period felt the same self-loathing expressed by the play's lead character, Michael. There is a seminal quote from Michael which is difficult to defend: "If only we could learn to stop hating ourselves so much." This is an exclamation difficult to justify, and one which I have trouble overlooking.

Michael indeed seems to be a self-hating homo, and I have no problem with such a character being portrayed onstage, we've seen many of them over the years. But he doesn't speak only of himself; he doesn't say "If only I could learn to stop hating MYself so much." He says "We" and "OURselves," suggesting to the world that all gay men despise themselves. This is not true today, nor was it true in 1968.

Though the performances surrounding them cannot be faulted, I'm sorry to say that I was disappointed in the work of stars Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto. Parsons has a congenial quality which simply cannot sustain the vicious behavior of his character Michael. And Quinto's entrance late in the play actually saps the energy in the room.

The real surprise in the second part of this play comes from one of my favorite stage actors, Andrew Rannells.

He is playing Larry, a role which was quite forgettable in the film, one half of the only gay couple in the piece. Larry is the guy who picks up a different trick every night and has no desire to settle into a hetero-normative relationship.

But he has reluctantly fallen for the conservative Hank, a school teacher with kids who has recently left his wife but is looking to replace that marriage with a similar one with a same sex partner.

This subplot is dull as toast in the film, I'm sorry to say, but in this production, Rannells's sparkle moves it front and center. The sequence in which these two mismatched lovers declare their commitment to each other is, for me, the highlight of the show's second half.

A word should be said about Charlie Carver as Cowboy, who appears to be making his professional stage debut in this production. I remember this kid from Desperate Housewives, and apparently he's maintained a lively career in TV/film (it has helped that he has an identical twin, they have often worked together).

Carver's role of the hustler is pretty one-note, though you can feel the audience turn against Michael when he makes snide comments about this poor kid's lack of intelligence. But Carver's final moments onstage are pretty poignant. As they are leaving, Harold asks his hooker how he is in bed. "I try to be a little affectionate," he replies. "It helps me feel less like a whore."

The Boys in the Band is going to carry its legacy as a groundbreaking play despite the debate regarding its central theme. This Broadway production is a worthy revival of this problematic piece. I can't help but think about those actors in the original production, back in 1968. We now know that five of them were gay, all of whom died during the Aids epidemic. The original director and producer were also taken.

The first thing I can report about the Broadway production of Boys in the Band is this: it's friggin' hilarious. Somehow, the same text which comes off as vicious on film becomes enjoyably flippant onstage, at least initially.

Congratulations in no small part must go to director Joe Mantello, who has guided his cast to mine the laughs, and they have struck gold. The first half of the show (in what used to be its first act; playwright Mart Crowley has wisely trimmed the play a bit and removed the intermission) feels like Terrence McNally wrote it. Jim Parsons as Michael, the leading character, knows his way around comedy, and his first scene, opposite Matt Bomer, is full of laughs.

Except it can't. Many gay men of the generation depicted in this play have accused the playwright of displaying some very nasty stereotypes, as if all gay men of the period felt the same self-loathing expressed by the play's lead character, Michael. There is a seminal quote from Michael which is difficult to defend: "If only we could learn to stop hating ourselves so much." This is an exclamation difficult to justify, and one which I have trouble overlooking.

Michael indeed seems to be a self-hating homo, and I have no problem with such a character being portrayed onstage, we've seen many of them over the years. But he doesn't speak only of himself; he doesn't say "If only I could learn to stop hating MYself so much." He says "We" and "OURselves," suggesting to the world that all gay men despise themselves. This is not true today, nor was it true in 1968.

Though the performances surrounding them cannot be faulted, I'm sorry to say that I was disappointed in the work of stars Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto. Parsons has a congenial quality which simply cannot sustain the vicious behavior of his character Michael. And Quinto's entrance late in the play actually saps the energy in the room.

The real surprise in the second part of this play comes from one of my favorite stage actors, Andrew Rannells.

|

But he has reluctantly fallen for the conservative Hank, a school teacher with kids who has recently left his wife but is looking to replace that marriage with a similar one with a same sex partner.

|

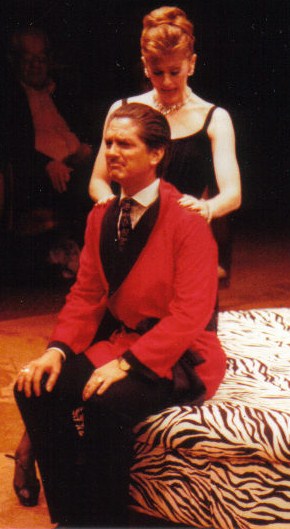

A word should be said about Charlie Carver as Cowboy, who appears to be making his professional stage debut in this production. I remember this kid from Desperate Housewives, and apparently he's maintained a lively career in TV/film (it has helped that he has an identical twin, they have often worked together).

|

|

| Charlie Carver came out publicly several years ago, and has an interesting story. His parents divorced when he was quite young, and he only found out later that the split was due to his father's homosexuality. His own coming out must have been fraught with extra baggage. |

The Boys in the Band is going to carry its legacy as a groundbreaking play despite the debate regarding its central theme. This Broadway production is a worthy revival of this problematic piece. I can't help but think about those actors in the original production, back in 1968. We now know that five of them were gay, all of whom died during the Aids epidemic. The original director and producer were also taken.

|

If you've gotten this far, you're clearly interested in this landmark play; there is a fascinating documentary, made in 2011, which explores the various reactions to The Boys in the Band when it first arrived on the scene. It's worth checking out, if only to hear how the play affected some younger playwrights such as Tony Kushner while it infuriated some of Crowley's contemporaries, such as Edward Albee. Here's the trailer for that documentary:

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)