|

| The reviews were stellar, with all of them saying how lucky Queens was, to have Titan Theatre in their midst. I was lucky, too, to have been a part of this remarkable production. |

I found at least two modern productions in which the Fool was a British Music Hall performer, to which the Fool's various songs lend themselves. In more than one production, the Fool is ultimately murdered by Lear himself, in a fit of madness. I'm not sure how the text supports that, but it's happened.

What has concerned directors of Lear over the years is the Fool's sudden disappearance, without explanation, in the middle of the play. In his final speech, Lear himself clears up the mystery by explaining his fool has been hanged, but there is no mention of exactly how or why the hanging might have taken place, or by whom. There is no other mention of his disappearance. It was decided in our production that I would be strangled and dragged offstage.

But I was never really concerned with how the Fool's life ended, I was more worried about giving life to the guy in the first place. For a full year, each and every time I mentioned to somebody, ANYbody, that I was to play the Fool in King Lear, that person's face lit up. "A great role!" or "Perfect for you!" or the like. Nice, right? The expectations of the Fool were very high, and even after a year of thought, I didn't know what the hell I was going to do with this part.

|

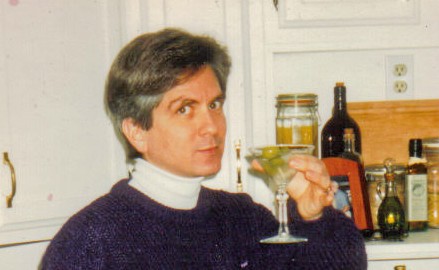

| Michael Selkirk as the blinded Gloucester, being led, unknowingly, by his son Edgar. I spent some time onstage with Brendan Marshall-Rashid as he played that convincing beggar, Poor Tom; his was an extremely physical and satisfying portrayal. And I say that even when he had his clothes ON. I played Gloucester a year ago for Hudson Warehouse (go here for that report), but this is the remarkable thing about Shakespeare: never once did I think of how I played the role, I was so engulfed in creating my own character of the Fool. And Michael's performance as Gloucester was deservedly congratulated. |

|

| Kevin Beebee, on the left, has used his business skills to help Titan grow fast and well. |

You really cannot go into pre-production hoping to find your King Lear at an audition (Hamlet is another of those roles; because the entire play really revolves around these characters, it is impossible to build an ensemble to effectively tell the story without first knowing who will be at the center of it all. This doesn't seem to be true with all Shakespeares. I think you can pre-plan Romeo and Juliet without knowing exactly who will be playing those title characters).

I did not personally know our Lear, Terry Layman, before we began, but I had seen his work as Friar Laurence in Titan's production of Romeo and Juliet. (We almost worked together in that production, but that's another story altogether.)

|

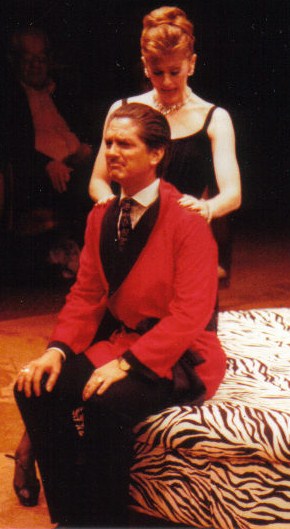

| Lear surrounded by his daughters, played by Laura Frye, Susan Maris, and Leah Gabriel. Fine actresses all, and they actually looked like a family! |

Lenny did a fabulous job editing this monster of a script, which in its full form runs 4 hours or so. Our cut ran only 2, yet told the full story with depth and nuance. And it's a good thing the edit was so drastic, as we had only three or so weeks to rehearse the show. We began, as so often happens, with the table reading on the first night.

Titan's King Lear was the troupe's inaugural production at their new home, the Queens Theatre, located in Corona Park, very near the stadium where the Mets play. The park is a lovely one, and it's peppered with huge structures which are both attractive and desolate.

|

|

| Our theatre is nestled in the midst of the aging monuments, above. |

Our show was produced in the Studio Theatre of the building which houses a larger main stage. It is a true Black Box, built as such, and it was a delight and a relief to be performing there. This King Lear was my seventh production in the two years I have had a New York Branch, and the only one to be performed in a space originally designed to be a theatre.

It was very nice to have actual dressing rooms, an actual Green Room, and the like, but really, if a show is good, it doesn't much matter where it is performed. And Titan's King Lear was very, very good, featuring a central performance which was majestic, funny, and ultimately heartbreaking. I was proud to be a part of it all.

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)