Gone With The Wind is one of my guilty favorites. Guilty, I suppose, because its depiction of happy Negroes working in the fields and waiting on the white folk with a song in their heart and a skip in their step, seems pretty insensitive, if not downright racist. And historically inaccurate, too. But GWTW has crossed my path several times this week, so it is only natural that the Dance Party be plucked from that masterful melodrama. We begin, as we so often do on Fridays, with a corpse:

Cammie King

1934-2010

1934-2010 She had a long career as a publicist and a museum director, but she will forever be remembered for her performance in Gone With the Wind. She often joked that her career "peaked at 5," and she was right. Other than a voice-over role in Disney's Bambi, our Cammie is remembered solely as Miss Eugenia Victoria, otherwise known as Bonnie Blue Butler.

She had a long career as a publicist and a museum director, but she will forever be remembered for her performance in Gone With the Wind. She often joked that her career "peaked at 5," and she was right. Other than a voice-over role in Disney's Bambi, our Cammie is remembered solely as Miss Eugenia Victoria, otherwise known as Bonnie Blue Butler.

She snagged the role of the only child of Rhett Butler and Scarlett O'Hara over a hundred other girls, she later reported, but that cannot be verified.

Apocryphal stories abound regarding the casting of this small but pivotal role: it's said that Shirley Temple was courted, but was too old by the time filming actually commenced (this story does not ring true to me, as Cammie King was paid a lousy $1000 for her participation, and Temple was the biggest star in Hollywood in 1939. Plus, the role has only a couple of short scenes, it seems doubtful Temple's handlers would ever consider such a part for their star).

Apocryphal stories abound regarding the casting of this small but pivotal role: it's said that Shirley Temple was courted, but was too old by the time filming actually commenced (this story does not ring true to me, as Cammie King was paid a lousy $1000 for her participation, and Temple was the biggest star in Hollywood in 1939. Plus, the role has only a couple of short scenes, it seems doubtful Temple's handlers would ever consider such a part for their star). It's also said that a young and fairly unknown Elizabeth Taylor was up for the part, but she also outgrew the role during the long pre-production period. Whatever the real truth, Cammie King's death last year leaves us with only two surviving performers from GWTW:

It's also said that a young and fairly unknown Elizabeth Taylor was up for the part, but she also outgrew the role during the long pre-production period. Whatever the real truth, Cammie King's death last year leaves us with only two surviving performers from GWTW:  Ann Rutherford, who played the small role of Carreen O'Hara (youngest sister to Scarlett) and of course, Olivia DeHaviland, who retired to France decades ago and is still hanging on (she turns 95 next week).

Ann Rutherford, who played the small role of Carreen O'Hara (youngest sister to Scarlett) and of course, Olivia DeHaviland, who retired to France decades ago and is still hanging on (she turns 95 next week).

I just went scouring through my bookcases, looking for my copy of Gone With the Wind, which I read twice as a teenager, and again in my 20s, but I guess I've lost it along the way.

It was a real page turner, despite its gigantic length. It was a sensational success as soon as it was published, 75 years ago this year. There are great stories about its diminutive author, Margaret Mitchell, and her slapdash writing habits and lack of organizational skills. She was a newspaper reporter in the 30s, highly unusual for a female, and GWTW was her only work of fiction.

It was a real page turner, despite its gigantic length. It was a sensational success as soon as it was published, 75 years ago this year. There are great stories about its diminutive author, Margaret Mitchell, and her slapdash writing habits and lack of organizational skills. She was a newspaper reporter in the 30s, highly unusual for a female, and GWTW was her only work of fiction.  She claimed she wrote the last chapter first, then wrote pieces of the story out of sequence, and turned them in to her publisher that way. Somebody did an heroic job of pulling the massively disorganized jumble of chapters into a coherent whole, but it was worth the effort. The book was a sensation, and cried out for a film version, even as turning such a sprawling behemoth into a 90 minute film seemed impossible.

She claimed she wrote the last chapter first, then wrote pieces of the story out of sequence, and turned them in to her publisher that way. Somebody did an heroic job of pulling the massively disorganized jumble of chapters into a coherent whole, but it was worth the effort. The book was a sensation, and cried out for a film version, even as turning such a sprawling behemoth into a 90 minute film seemed impossible.  Turned out it was, as the final cut of the film runs 4 hours with a full intermission, and even then, major characters and plotlines from the novel were cut. Large flashback sequences involving Scarlett's parents were eliminated, as was the interesting but incidental examination of Rhett's family in Charleston.

Turned out it was, as the final cut of the film runs 4 hours with a full intermission, and even then, major characters and plotlines from the novel were cut. Large flashback sequences involving Scarlett's parents were eliminated, as was the interesting but incidental examination of Rhett's family in Charleston. Did you know that Bonnie Blue Butler was not Scarlett's only child? Our author Margaret Mitchell gave our heroine a son with her first husband, and a daughter with her second. Both were jettisoned from the film, as were Ashley's second sister

Did you know that Bonnie Blue Butler was not Scarlett's only child? Our author Margaret Mitchell gave our heroine a son with her first husband, and a daughter with her second. Both were jettisoned from the film, as were Ashley's second sister  (the film suggests Ashley's only sibling to be the embittered old maid India Wilkes) and Archie, an itinerant Confederate soldier who becomes part of the post-war inhabitants of the plantation Tara.

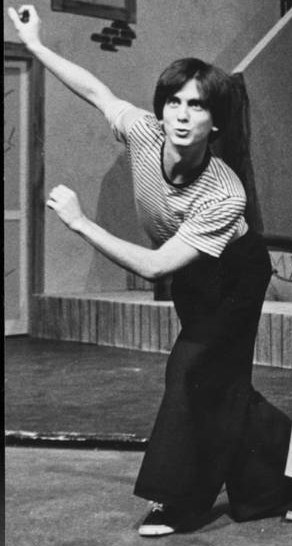

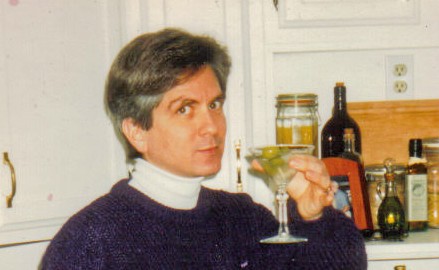

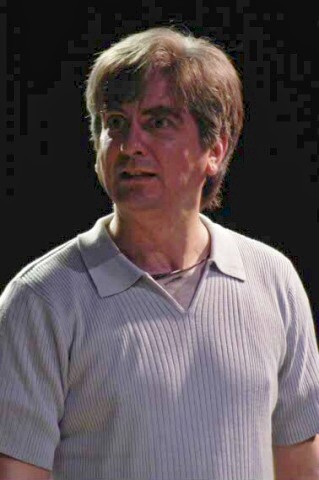

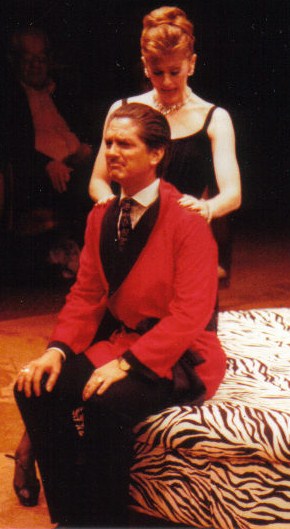

(the film suggests Ashley's only sibling to be the embittered old maid India Wilkes) and Archie, an itinerant Confederate soldier who becomes part of the post-war inhabitants of the plantation Tara.The story of how this massive melodrama was turned into one of the most successful films in history, is told in a delightful little play currently making the rounds of regional theaters around the country. I caught Moonlight and Magnolias at Totem Pole Playhouse this week, yet another reason GWTW is the star of this week's Dance Party.

The play is a fun snapshot of the writing of the film, and takes a fictional look at a real occurrence. After three weeks of shooting, producer David O. Selznick shut down production (at a huge financial cost), fired director George Cukor, replacing him with Clark Gable's best buddy Victor (The Wizard of Oz) Fleming, and sent the script back to rewrite.

Moonlight and Magnolias wonders what would happen if Selznick had locked his new director, his script doctor, and himself, into an office for a week, to rewrite the script. Totem Pole's production is a hoot; a harried secretary, a writer who has not read the book, and a major sprinkling of peanuts and bananas all add up to a very funny play. In between laughs, though, Moon & Mags touches upon a controversy which actually erupted when GWTW was first published (and the discussion continues to this day).

Moonlight and Magnolias wonders what would happen if Selznick had locked his new director, his script doctor, and himself, into an office for a week, to rewrite the script. Totem Pole's production is a hoot; a harried secretary, a writer who has not read the book, and a major sprinkling of peanuts and bananas all add up to a very funny play. In between laughs, though, Moon & Mags touches upon a controversy which actually erupted when GWTW was first published (and the discussion continues to this day).  Though it won the Pulitzer Prize, the novel is often pointed to as an example of revisionist, racist thinking. In the book, the slaves are quite happy with their station in life; Mitchell defended her story by pointing out that the black characters were the most honorable in the book. She is right, but she skates over the fact that slaves were often tortured, starved, and separated from their families.

Though it won the Pulitzer Prize, the novel is often pointed to as an example of revisionist, racist thinking. In the book, the slaves are quite happy with their station in life; Mitchell defended her story by pointing out that the black characters were the most honorable in the book. She is right, but she skates over the fact that slaves were often tortured, starved, and separated from their families.  The slaves at Tara were happy darkies, content to serve their white masters. That assumption is a little difficult to swallow, as is the repulsively positive way in which Mitchell treats the KKK.

The slaves at Tara were happy darkies, content to serve their white masters. That assumption is a little difficult to swallow, as is the repulsively positive way in which Mitchell treats the KKK. But Gone With the Wind remains a favorite of mine anyway. This week's Dance Party comes from the Atlanta Bazaar scene, in which an auction is held to raise money for the Confederate Army. Our heroine has been widowed, by her first husband whom she married on the rebound, so she is in public mourning.

But Gone With the Wind remains a favorite of mine anyway. This week's Dance Party comes from the Atlanta Bazaar scene, in which an auction is held to raise money for the Confederate Army. Our heroine has been widowed, by her first husband whom she married on the rebound, so she is in public mourning.  It's fun to watch the close-ups of Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable as they dance; Gable was a pretty lousy dancer, which was just as well, as camera angles required that platforms were constructed for him and Leigh to stand upon during much of their dialogue. Unseen stage hands swayed the platforms to suggest that Rhett and Scarlet were sweeping across the dance floor while having their flirtatious conversation. In fact, for much of the time, they were standing still.

It's fun to watch the close-ups of Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable as they dance; Gable was a pretty lousy dancer, which was just as well, as camera angles required that platforms were constructed for him and Leigh to stand upon during much of their dialogue. Unseen stage hands swayed the platforms to suggest that Rhett and Scarlet were sweeping across the dance floor while having their flirtatious conversation. In fact, for much of the time, they were standing still.-

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)