I have confessed previously to have seen the musical revue Side by Side by Sondheim twice in a single week, due to the presence in the cast of Nancy Dussault and Hermione Gingold. Well, this is the week in which I did that unusual, slightly disturbing thing. In my own defense, the cast was top-notch, and Sondheim's music always benefits from repeated hearings.

I attended two other musicals that week in 1977, both of which held surprises for me.

I enjoyed the heck out of I Love My Wife for a few reasons. The comic lead was a gangly livewire named Lenny Baker, who had already won a Tony for this role. He dominated the show, but not to the exclusion of a sedate, subtle young woman making her Broadway debut. In a largely reactive role, Joanna Gleason made such an impression on me that I left the theatre wondering who the hell she was (according to the program, here is one of the things she was: Monty Hall's daughter, a fact which seems missing from her subsequent bios).

Nobody ever does I Love My Wife these days, despite its being a relatively small-cast show (only four principals, and an on-stage band; no orchestra needed) with a fun-filled score by Cy Coleman. It's very much a Period Piece, that period being the swinging 70s. I Love My Wife is about wife-swapping.

The other musical I saw that year was one of the biggest hits of the decade. I thoroughly enjoyed Annie, though for the first 20 minutes or so, I was confused. Not by the story, which was simplicity itself, but by the casting of a milque-toast young girl named Andrea McArdle in the title role. In those early scenes in the orphanage, she literally vanished among the group of livelier kids, who always took the focus from her. But about 20 minutes into the show, sitting on the floor of a blank stage, in a pinspot, with Sandy the dog curled up at her side, she revealed why she was in the show. As that anthem of optimism, Tomorrow, was belted by that naive little pre-teen, I swear the lighting fixtures in the theatre started to quiver. By the time she hit those final phrases, the walls were shaking, the seats were vibrating, and the audience's mouths were open.

Nobody could believe such a sound was coming out of such a young human.

McArdle was nominated for a Tony, but lost it, quite rightly, to her co-star, a woman who had been knocking around Broadway for years, appearing in flop after flop. With Annie, Dorothy Loudon became the success she had always deserved to be. Every comic moment landed perfectly in her performance, and her showstopping number, Easy Street, remains one of the most dynamic songs I have ever witnessed onstage.

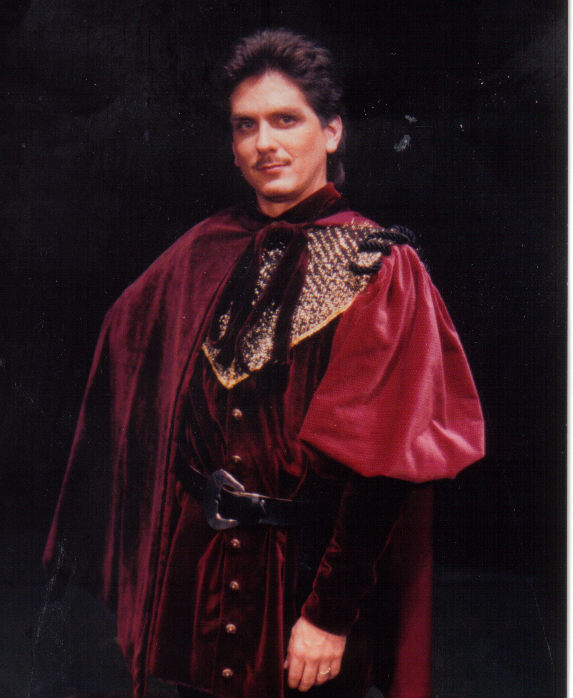

I saw two straight plays during that trip, both of which were dominated by the star at their center. Frank Langella received raves for his reinterpretation of Count Dracula as a sexual being, and I have to admit his suave performance was a far cry from Bela Lugosi. Still, I don't remember much about this production, which was the basis for a movie version co-starring Laurence Olivier.

But this was one instance where I fulfilled that old adage, and left the theatre "humming the set." The design elements of Dracula, both sets and costumes, were handled by Edward Gorey, who was primarily known as the author of macabre short stories and cartoons. The Addams Family television series was in part based on his caricatures, and his drawings can still be seen in the opening credits of PBS's Mystery.

The last show I saw during this trip was my first George Bernard Shaw play, a production of Saint Joan, with Lynn Redgrave in the lead (and Robert LuPone, fresh from A Chorus Line, in support). I couldn't have known at the time that I would be meeting and, for one night, studying with Ms. Redgrave, almost 20 years later. While I was interning at The Shakespeare Theatre Company in DC, Redgrave came to town specifically to conduct a Master Class for the younger members of the company. But there was a twist: this "class" took place in front of 400 patrons who had paid dearly for the chance to watch Lynn Redgrave teach. There were only a handful of us actors involved, all of whom performed a Shakespearean monologue. Redgrave was a truly gracious coach, and the evening was a successful one, partially due to her ability to calm our nerves in the green room before the class began. She brought out a slim volume of Shakespeare which had belonged to her father, Sir Michael Redgrave, and explained that she never went onstage without spending a moment holding this worn, dog-eared, cloth-bound book. We all took our turn with this mysterious ritual; we were not about to decline this chance to participate in such a Redgravian tradition.

The last show I saw during this trip was my first George Bernard Shaw play, a production of Saint Joan, with Lynn Redgrave in the lead (and Robert LuPone, fresh from A Chorus Line, in support). I couldn't have known at the time that I would be meeting and, for one night, studying with Ms. Redgrave, almost 20 years later. While I was interning at The Shakespeare Theatre Company in DC, Redgrave came to town specifically to conduct a Master Class for the younger members of the company. But there was a twist: this "class" took place in front of 400 patrons who had paid dearly for the chance to watch Lynn Redgrave teach. There were only a handful of us actors involved, all of whom performed a Shakespearean monologue. Redgrave was a truly gracious coach, and the evening was a successful one, partially due to her ability to calm our nerves in the green room before the class began. She brought out a slim volume of Shakespeare which had belonged to her father, Sir Michael Redgrave, and explained that she never went onstage without spending a moment holding this worn, dog-eared, cloth-bound book. We all took our turn with this mysterious ritual; we were not about to decline this chance to participate in such a Redgravian tradition.The theatrical voodoo worked, and that evening remains one of the most exciting and fulfilling I have ever spent on any stage, anywhere.

A few years later, Lynn premiered her one-woman show, Shakespeare for My Father, which dealt with her complicated relationship with her dad, and I'm sure she spent a moment backstage before every performance with that slender volume she inherited from him. I imagine she did the same back in 1977, right before that performance of Saint Joan which introduced me to Shaw, and to this extraordinary actress.

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

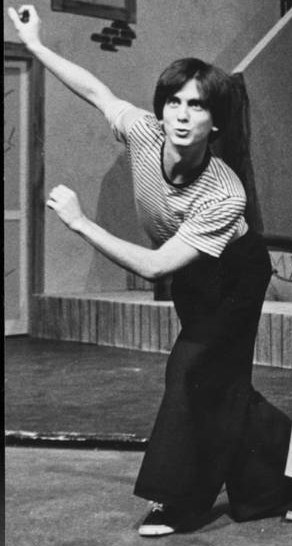

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)