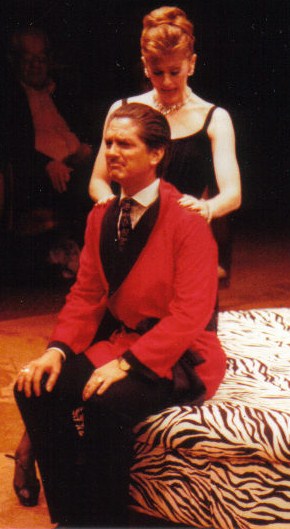

Farley Granger (at right with Roddy McDowell) and Lanford Wilson both died weeks and weeks ago, but still deserve some notice.

I think the first time I became aware of Lanford Wilson was in my undergraduate days, when my friend Janie appeared in one of his lesser known one-acts, The Great Nebula in Orion. It was a fairly plotless character study of two women, and even then, I could see that this guy wrote for actors. In fact, I doubt you could find an American stage actor who will turn down a role in a Lanford Wilson play; his characters provide brilliant showcases for the kind of Method-based acting  in which American actors excel. His work is full of what is sometimes called "lyric realism," everyday language which is somehow heightened to become the poetic.

in which American actors excel. His work is full of what is sometimes called "lyric realism," everyday language which is somehow heightened to become the poetic.

Wilson is often credited with being one of the creators of the Off-Off-Broadway movement, as his work presented at the Cafe Cino in the early 60s brought mainstream attention to the barebones, raw productions happening in basements, cafes, and crummy storefronts all over New York. His one-act The Madness of Lady Bright became a substantial hit, running hundreds of performances, and is now recognized as one of the first commercial successes to be found Off-Off-. It is also known as one of the first benevolent portrayals of the gay lifestyle.

Lanford was himself gay, and he presented gay characters in several of his plays, including the gay couple at the center of Fifth of July, and his most autobiographical work, Lemon Sky. But he can in no way be classified strictly as a gay playwright. His early full-length works are sprawling canvases with dozens of characters who have come together to form a Family of the Downtrodden or Disenfranchised. Balm in Gilead and Hot L Baltimore follow this pattern, and are rarely revived today due to their large casts. In 1984, Steppenwolf Theatre brought their revival of Balm in Gilead to Off-Broadway; Laurie Metcalf won an Obie for her scene-stealing 20 minute monologue in act II, in a performance which launched her national career.

Lanford Wilson's resume includes dozens of full-length plays, one-acts, and even operas, but he is probably best known for his "Talley Trilogy." In 1978, he penned Fifth of July, which concerned the Talley family of Missouri, and which many consider to be his breakout work. While in rehearsal for the show, the story goes, actress Helen Stenborg, playing elderly Aunt Sally, asked the playwright about her character's backstory. (Helen died recently as well, go here for my obit)

Specifically, she was interested in Sally's marriage, which had ended with her husband's death and from which Sally was still reeling (in Fifth of July, Aunt Sally still carries her husband's ashes around in a candy box). Stenborg's questions sparked Wilson's creative juices, and he set about investigating the courtship of the young Sally and her husband. The resulting play, Talley's Folly, won the Pulitzer. Wilson followed up with A Tale Told, which was later revised to become Talley and Son.

Specifically, she was interested in Sally's marriage, which had ended with her husband's death and from which Sally was still reeling (in Fifth of July, Aunt Sally still carries her husband's ashes around in a candy box). Stenborg's questions sparked Wilson's creative juices, and he set about investigating the courtship of the young Sally and her husband. The resulting play, Talley's Folly, won the Pulitzer. Wilson followed up with A Tale Told, which was later revised to become Talley and Son. Though many of his plays made it to Broadway, Wilson's work was usually better showcased Off-Broadway and in regional theaters. He had a strong relationship with New York's Circle Rep (in fact, he was one of the founders), and his contributions

to Steppenwolf in Chicago provided a starry turn for a young John Malkovich in Burn This. Late in his career, he spent time with the Purple Rose Theater in Michigan, for whom he wrote his final two plays.

to Steppenwolf in Chicago provided a starry turn for a young John Malkovich in Burn This. Late in his career, he spent time with the Purple Rose Theater in Michigan, for whom he wrote his final two plays.As I mentioned, Wilson's plays are catnip for American actors;

Fifth of July was on my wish list for years, but Christopher Reeve, Richard Thomas, William Hurt, Michael O'Keefe, Timothy Bottoms, and Robert Sean Leonard got there first. The list of actors who displayed major acting chops in Wilson's plays includes Swoozie Kurtz (Fifth of July),

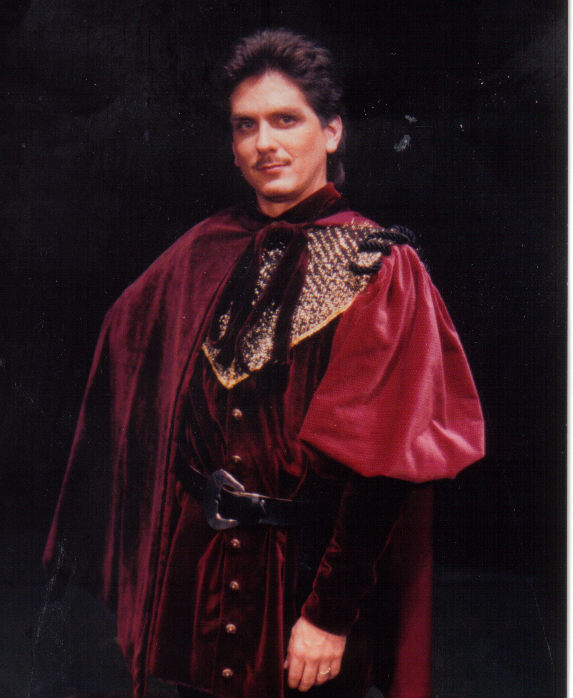

Fifth of July was on my wish list for years, but Christopher Reeve, Richard Thomas, William Hurt, Michael O'Keefe, Timothy Bottoms, and Robert Sean Leonard got there first. The list of actors who displayed major acting chops in Wilson's plays includes Swoozie Kurtz (Fifth of July),  Judd Hirsch (Talley's Folly), and Jeff Daniels, who took three of Wilson's plays to Broadway. The aforementioned Helen Stenborg won an Obie for Talley and Son, as did this guy:

Judd Hirsch (Talley's Folly), and Jeff Daniels, who took three of Wilson's plays to Broadway. The aforementioned Helen Stenborg won an Obie for Talley and Son, as did this guy:Farley Granger

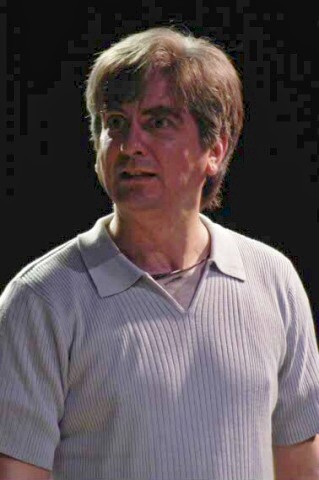

Granger was appearing Off-Broadway in 1985 because, decades earlier, he ditched his blooming film career in order to become a stage actor.  He had reached the peak of his celebrity very early in his career, with starring roles in two Hitchcock films, Rope and Strangers On A Train. He became disenchanted with the studio system and yearned for the footlights instead, so in 1953, he bought out the final two years of his film contract and headed to New York. New York shrugged,

He had reached the peak of his celebrity very early in his career, with starring roles in two Hitchcock films, Rope and Strangers On A Train. He became disenchanted with the studio system and yearned for the footlights instead, so in 1953, he bought out the final two years of his film contract and headed to New York. New York shrugged,  so Farley took an unusual step for an established movie star: he went to school to learn to act. After studying at the Neighborhood Playhouse, he took roles in regional theatre and Off-Broadway, finally making it to The Great White Way in First Impressions, the musical version of Pride and Prejudice. That show worked about as well as you would think, and lasted less than 100 performances. Our hero followed it up with another failure, The Warm Peninsula, which at least allowed him to star with Julie Harris, June Havoc, and a young Larry Hagman. Granger supplemented his income with appearances on television during the Golden Age, playing opposite Ms. Harris in The Heiress, among other highbrow works. Back onstage, he was well-received as John Proctor in The Crucible in 1964, and as the king in The King and I opposite Barbara Cook in 1960 (for the latter, one critic noted "Granger comes to the revival with a fresh point of view and a full head of hair").

so Farley took an unusual step for an established movie star: he went to school to learn to act. After studying at the Neighborhood Playhouse, he took roles in regional theatre and Off-Broadway, finally making it to The Great White Way in First Impressions, the musical version of Pride and Prejudice. That show worked about as well as you would think, and lasted less than 100 performances. Our hero followed it up with another failure, The Warm Peninsula, which at least allowed him to star with Julie Harris, June Havoc, and a young Larry Hagman. Granger supplemented his income with appearances on television during the Golden Age, playing opposite Ms. Harris in The Heiress, among other highbrow works. Back onstage, he was well-received as John Proctor in The Crucible in 1964, and as the king in The King and I opposite Barbara Cook in 1960 (for the latter, one critic noted "Granger comes to the revival with a fresh point of view and a full head of hair").

He also spent many months in the long-running Deathtrap.

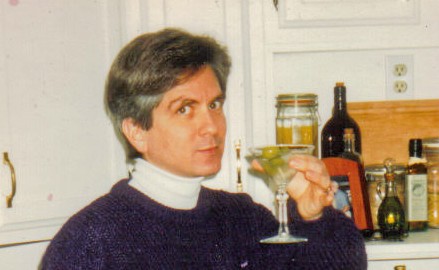

As Farley aged, he became more loose-lipped about his personal life, which would make a great miniseries for Showtime.

He had a long, on-and-off-again romance with Shelley Winters, and was connected with several other actresses including Ava Gardner, but his autobiography reveals that he also had affairs with men, including Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Laurents.

He had a long, on-and-off-again romance with Shelley Winters, and was connected with several other actresses including Ava Gardner, but his autobiography reveals that he also had affairs with men, including Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Laurents.

His longest personal relationship was with Robert Calhoun, who died in 2006. When Granger died last month, he was 85 and left no survivors.

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

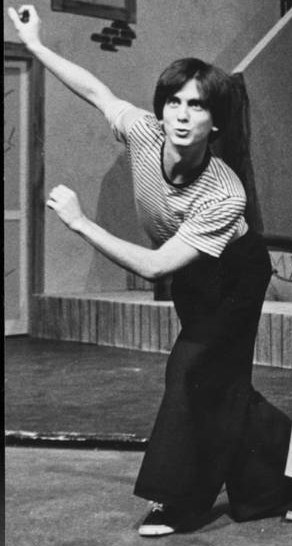

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)