|

|

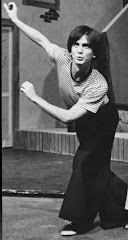

| Earliest known shot of my mother and me. |

We did not hire home care, which would have been the last thing my mother wanted: to have a stranger bustling around her at this intimately private moment. We set about doing Home Care on our own. My older sister Laura, who lived in Atlanta, flew out to Los Angeles. She was a homemaker, in an age when that species was pretty much extinct, so she was the one usually making the meals and running that aspect of the house. My younger sister Joan, who was studying at UCLA at the time, and living on campus, stopped going to class and moved home. She slept on the floor next to my mother's bed, and spent a lot of time in the room with her.

|

| My sisters shared the workload of caring for my mother in her last weeks. Here, they shared a pizza. |

.jpg) |

| The oxygen tank which sat next to Mom's bed looked a lot like this, but with valves and gauges. It was impossible to pretend all was well with this thing whirring away. |

I didn't do much during this period, other than keep tabs on the oxygen levels, and arrange for the tanks to be exchanged when needed. My sisters handled most of the daily tasks associated with caring for my mother. I took my turn, you see, the previous ten years.

|

| 1974, my senior year of high school, coincided with the first year of my mother's cancer diagnosis. |

|

| I can't imagine how my father coped. During Mom's final weeks, he was forced into making "final arrangements": funeral, cremation, interment, all while watching his life partner drift away. |

I lived at home all through that decade, while little sis Joan eventually moved on campus and big sis Laura maintained her own family across the country. Most of those years, our family lived a relatively normal, uneventful life. After college (during which, as I said, I lived at home), I was working two part-time jobs, as a waiter and as a customer service clerk at Sears, while doing shows at night. So I can't claim to have spent a huge amount of time with my mother during those years, except that I slept there. And ate there. And sat many times with her, casually chatting away, not realizing how those moments would become special to me in memory.

We did have a routine for a while. I would come home from whichever job I had attended, often around 5 or 6. My father was a workaholic at Lockheed and was never expected home until much later in the evening. I would dash upstairs to check the messages on my phone machine (remember those?) and to change out of whichever uniform I had worn to whichever job that day: tie and slacks for Sears, dreary brown vest and sensible shoes for the restaurant.

After leaving me alone a little while, my mom, puttering around in the kitchen, would holler up the stairs to me, "Want a cocktail?" This was a running joke with us; our "cocktail hour" consisted of sharing a can of light beer while we chatted about our day (it was my mother, incidentally, who clued me in to the fact that you could get more head on your beer if you salted it. It's a trick I still use).

|

| This must have been during my teen years. I don't see any beer. |

|

| My mother is known as "Jo" to her grandkids. |

In another entry one day, I'll probably relate the story of the day my mother's cancer returned for the final time, about a year before she died, but I'll wait on that one. I have so many memories flying around my head this time of year. My mother was taken, as I mentioned, on March 28, which, in 1983, landed on the Monday between Palm Sunday and Easter; Christians call this Holy Week. This is a fairly unusual occurrence, as Easter is usually later in April. This year, 30 years later, March 28 once again falls during Holy Week. I'm not particularly religious, but I like to think that coincidence has some sort of cosmic significance.

|

| Jo was a hometown beauty, the first Apple Blossom Queen of Hendersonville, NC. She resembled Rita Hayward during this time; I wrote about that here. |

The atmosphere around the house was not as grim as you might imagine, during those final weeks 30 years ago. Joan did a great job of keeping my mother's spirits up as she became more and more bedridden. I remember one afternoon bounding up the stairs after my day shift at Sears, to the tune of dance music pounding from the master suite.

|

| As a married woman, Jo was often told she resembled Juliet Prowse; I wrote about that here. |

Michael Jackson's Thriller was the album of the day, and one of its many hits was playing on the radio. Mom was sitting up in bed, contentedly knitting or reading or something. Her feet under the covers were bopping around to the beat.

|

| Even bedridden, you had to dance to this album. |

|

| I was in rehearsal as Dr. Einstein in Arsenic and Old Lace during my mother's last weeks (I wrote about that experience here). If I hadn't had this goofy show to return to after her death, I wouldn't have made it. |

The oncologist in charge, one Dr. Chernoff by name, was an expert, I suppose, in losing patients, and his advice was to allow my mother to come to the realization on her own. So when we brought her home from the hospital in January of '83, she was under the impression that more treatment would be proscribed. Chernoff, to his credit (and believe me, I don't give him much) liked my mother enough to actually perform house calls, unheard of in modern times. During one such visit, I overheard Mom ask what the next step for her would be. He replied simply that she would be given some steroids to strengthen her and to make her more comfortable. A silence lingered after his answer, and I have a hunch it was at that moment that my mother began to realize she was not going to recover.

At one point, she surprised us by asking to see a minister. My parents were members of a local Presbyterian church, but did not by any means attend regularly. The minister there was happy to come out to see my mom. I brought him up to her room, and as I closed the door to give them privacy, I heard her demand, "So, do you really believe there is a heaven?"

Clearly, in a very private way, my mother was struggling with her truth. As I mentioned, she lived longer than the doctors predicted. As the days lengthened into weeks, Laura had to return home to tend to her own family. A few days more went by, and my mother stopped speaking much, and stopped eating at all.

I'm told this is quite common for terminal patients when they realize they are not going to survive. After several days went by, during which she refused all food, Laura returned to L.A., and we resumed The Wait. Ultimately, Mom began eating again; she must have come to some kind of peace in her own mind. I was sitting with her one afternoon, giving my sisters a break. She slept a lot during those last days, and the bed was so huge (and she was at that point very, very small) that I was lying on top of the covers on my father's side of the bed, reading. She turned over, from one side to the other, and murmured to no one in particular, "I'm so tired of this."

The evening of the 28th, she began to have substantial trouble breathing. She didn't seem to be getting enough oxygen, and I called our technician, asking for a better mask for her; she had been using one of those which put tubes up the nostrils. He hurried over with one of those over the mouth-and-nose things, but he arrived too late. I don't think it would have done much good. It was time.

But we were all there; my memory is crystal clear on the scene. My father was kneeling at the side of the bed, holding my mother's hand. Her eyes were transfixed on his. My sisters were sitting motionless, waiting for the inevitable. And me, I was standing up, but very still. I have to admit that we were not a particularly close family, the kids were raised to go our individual ways, but during this terrible period, we banded together. And at that moment, 30 years ago today, I'm sure we helped her. At the moment she died, we were all there. In a way, we were my mother's angels. And that gives me comfort.

|

| Joan "Jo" Williams 10/18/28 - 3/28/83 |

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)