The star of this week's Dance Party was never one of my favorites, though I always respected his talent. He popped up on my radar this week as I was writing my obit for Broadway librettist Joseph Stein, who furnished him with his Broadway debut, Mr. Wonderful. Sammy Davis, Jr. always seemed a little too showy for my tastes, but that attitude came naturally to him. He spent his entire life in show business, beginning with vaudeville appearances at the age of 3.

He faced down racial bigotry throughout his career, for which he deserves a lot of respect. He made his first splash as a nightclub performer; it's said that his performance at the after-party of the 1951 Oscar ceremony, at Ciro's nightclub, caused a sensation and brought him to the attention of the Show Business Greats. He was soon headlining in Vegas, but as a black man, was forced to leave the showroom after his performances and go across town to sleep in a boarding house, while white performers stayed as guests of the hotels which housed the showrooms.

Show Business Greats. He was soon headlining in Vegas, but as a black man, was forced to leave the showroom after his performances and go across town to sleep in a boarding house, while white performers stayed as guests of the hotels which housed the showrooms.

In 1954, driving from Vegas to Los Angeles after one of his gigs, he had a car accident which cost him one eye. He wore an eye-patch for a while, before receiving the glass eye for which he became famous (it was this car crash which also lead to his conversion to Judaism). By the late 50s, he had recorded several albums, and had become a member of an ad hoc clique of performers first started by Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Becall. By the time Davis joined, the group included Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford. The club also included some female stars, though they were treated more as mascots than as equal members. Shirley MacLaine, Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, and Angie Dickinson were a few of the dames the guys included. When Davis became a member, Sinatra was calling the group "the Clan," a moniker to which Sammy objected as being too closely related to the Ku Klux Klan. The name was changed within the group to "The Summit," but the press always referred to them as The Rat Pack.

group included Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford. The club also included some female stars, though they were treated more as mascots than as equal members. Shirley MacLaine, Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, and Angie Dickinson were a few of the dames the guys included. When Davis became a member, Sinatra was calling the group "the Clan," a moniker to which Sammy objected as being too closely related to the Ku Klux Klan. The name was changed within the group to "The Summit," but the press always referred to them as The Rat Pack.

Sammy had several songs hit the Billboard charts over the years, including "What Kind of Fool

Sammy had several songs hit the Billboard charts over the years, including "What Kind of Fool Am I?" ( a tune from Broadway's Stop the World, I Want to Get Off), which hit #11, and a surprise #1 smash from the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, "The Candy Man." But I recall Davis getting lots of traction with his rendition of "Mr. Bojangles," which he sang on many variety shows in the 70s and beyond. He would always include a smooth soft-shoe to accompany this song of a guy sitting in a drunk tank with a homeless bum who could dance.

Am I?" ( a tune from Broadway's Stop the World, I Want to Get Off), which hit #11, and a surprise #1 smash from the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, "The Candy Man." But I recall Davis getting lots of traction with his rendition of "Mr. Bojangles," which he sang on many variety shows in the 70s and beyond. He would always include a smooth soft-shoe to accompany this song of a guy sitting in a drunk tank with a homeless bum who could dance.

Sammy won a Tony nomination for his performance in Golden Boy in 1964, and Emmy nominations for guest appearances in The Cosby Show and daytime's One Life to Live. He made a cameo appearance as himself in the first season of All in the Family, and created a legendary moment by kissing the bigot Archie Bunker on the cheek. His commemorative special Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration won the Emmy in 1990, though Davis himself had died several months earlier. He has a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys and a Kennedy Center Honor.

Sammy won a Tony nomination for his performance in Golden Boy in 1964, and Emmy nominations for guest appearances in The Cosby Show and daytime's One Life to Live. He made a cameo appearance as himself in the first season of All in the Family, and created a legendary moment by kissing the bigot Archie Bunker on the cheek. His commemorative special Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration won the Emmy in 1990, though Davis himself had died several months earlier. He has a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys and a Kennedy Center Honor.

But he always felt that his race set him apart from the other Rat Packers (he was the only black member), and he never stopped fighting for civil rights. He attended Martin Luther King's March on Washington, and was a supporter of Jesse Jackson's presidential campaign. He was asked on the golf course once, by Jack Benny in fact, what his handicap was. "Handicap? " he replied, "How's this for a handicap? I'm a one-eyed Negro Jew."

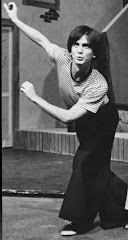

Davis died 20 years ago this summer, after a vicious battle with throat cancer (he was a lifelong smoker). For this week's Dance Party, please enjoy one of the first film appearances of Sammy Davis, Jr.:

He faced down racial bigotry throughout his career, for which he deserves a lot of respect. He made his first splash as a nightclub performer; it's said that his performance at the after-party of the 1951 Oscar ceremony, at Ciro's nightclub, caused a sensation and brought him to the attention of the

Show Business Greats. He was soon headlining in Vegas, but as a black man, was forced to leave the showroom after his performances and go across town to sleep in a boarding house, while white performers stayed as guests of the hotels which housed the showrooms.

Show Business Greats. He was soon headlining in Vegas, but as a black man, was forced to leave the showroom after his performances and go across town to sleep in a boarding house, while white performers stayed as guests of the hotels which housed the showrooms.In 1954, driving from Vegas to Los Angeles after one of his gigs, he had a car accident which cost him one eye. He wore an eye-patch for a while, before receiving the glass eye for which he became famous (it was this car crash which also lead to his conversion to Judaism). By the late 50s, he had recorded several albums, and had become a member of an ad hoc clique of performers first started by Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Becall. By the time Davis joined, the

group included Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford. The club also included some female stars, though they were treated more as mascots than as equal members. Shirley MacLaine, Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, and Angie Dickinson were a few of the dames the guys included. When Davis became a member, Sinatra was calling the group "the Clan," a moniker to which Sammy objected as being too closely related to the Ku Klux Klan. The name was changed within the group to "The Summit," but the press always referred to them as The Rat Pack.

group included Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford. The club also included some female stars, though they were treated more as mascots than as equal members. Shirley MacLaine, Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Ava Gardner, and Angie Dickinson were a few of the dames the guys included. When Davis became a member, Sinatra was calling the group "the Clan," a moniker to which Sammy objected as being too closely related to the Ku Klux Klan. The name was changed within the group to "The Summit," but the press always referred to them as The Rat Pack. Sammy had several songs hit the Billboard charts over the years, including "What Kind of Fool

Sammy had several songs hit the Billboard charts over the years, including "What Kind of Fool Am I?" ( a tune from Broadway's Stop the World, I Want to Get Off), which hit #11, and a surprise #1 smash from the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, "The Candy Man." But I recall Davis getting lots of traction with his rendition of "Mr. Bojangles," which he sang on many variety shows in the 70s and beyond. He would always include a smooth soft-shoe to accompany this song of a guy sitting in a drunk tank with a homeless bum who could dance.

Am I?" ( a tune from Broadway's Stop the World, I Want to Get Off), which hit #11, and a surprise #1 smash from the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, "The Candy Man." But I recall Davis getting lots of traction with his rendition of "Mr. Bojangles," which he sang on many variety shows in the 70s and beyond. He would always include a smooth soft-shoe to accompany this song of a guy sitting in a drunk tank with a homeless bum who could dance. Sammy won a Tony nomination for his performance in Golden Boy in 1964, and Emmy nominations for guest appearances in The Cosby Show and daytime's One Life to Live. He made a cameo appearance as himself in the first season of All in the Family, and created a legendary moment by kissing the bigot Archie Bunker on the cheek. His commemorative special Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration won the Emmy in 1990, though Davis himself had died several months earlier. He has a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys and a Kennedy Center Honor.

Sammy won a Tony nomination for his performance in Golden Boy in 1964, and Emmy nominations for guest appearances in The Cosby Show and daytime's One Life to Live. He made a cameo appearance as himself in the first season of All in the Family, and created a legendary moment by kissing the bigot Archie Bunker on the cheek. His commemorative special Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration won the Emmy in 1990, though Davis himself had died several months earlier. He has a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys and a Kennedy Center Honor.

But he always felt that his race set him apart from the other Rat Packers (he was the only black member), and he never stopped fighting for civil rights. He attended Martin Luther King's March on Washington, and was a supporter of Jesse Jackson's presidential campaign. He was asked on the golf course once, by Jack Benny in fact, what his handicap was. "Handicap? " he replied, "How's this for a handicap? I'm a one-eyed Negro Jew."

Davis died 20 years ago this summer, after a vicious battle with throat cancer (he was a lifelong smoker). For this week's Dance Party, please enjoy one of the first film appearances of Sammy Davis, Jr.:

(The above is from the most recent revival, with its replacement cast of Andrea Martin and Harvey Fierstein)

(The above is from the most recent revival, with its replacement cast of Andrea Martin and Harvey Fierstein)

,+Olney+Theatre+Center,+2004.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Warehouse+Theatre,+1999.jpg)

,+Are.jpg)

,+Everyman+Theatre,2002.jpg)

,+First+Nationa.jpg)

,+Shakespeare+Theatre+Company,.jpg)

,+Granada+Th.jpg)

,+Globe+Playhouse,.jpg)

,+CSUN,+1976.jpg)